Artist’s representation of Milky Way Galaxy surrounded by dozens of stellar streams (Credit: James Josephides; S5 Collaboration).

Astronomers are one step closer to revealing the properties of dark matter enveloping our Milky Way galaxy, thanks to a new map of twelve streams of stars orbiting within our Galactic halo.

Understanding these star streams is very important for astronomers. As well as revealing the dark matter that holds the stars in their orbits, they also tell us about the formation history of the Milky Way, revealing that the Milky Way has steadily grown over billions of years by shredding and consuming smaller stellar systems.

“We are seeing these streams being disrupted by the Milky Way’s gravitational pull, and eventually becoming part of the Milky Way. This study gives us a snapshot of the Milky Way’s feeding habits, such as what kinds of smaller stellar systems it ‘eats’. As our Galaxy is getting older, it is getting fatter.” said University of Toronto Professor Ting Li, the lead author of the paper.

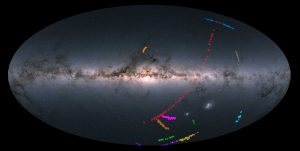

Location of the stars in the dozen streams as seen across the sky. The background shows the stars in our Milky Way from the ESA’s Gaia mission. The AAT is a Southern Hemisphere telescope so only streams in the Southern sky are observed by S5 (Credit: Ting Li, S5 Collaboration and European Space Agency).

Professor Li and her international team of collaborators initiated a dedicated program — the Southern Stellar Stream Spectroscopic Survey (S5) – to measure the properties of stellar streams: the shredded remains of neighboring small galaxies and star clusters that are being torn apart by our own Milky Way.

Li and her team are the first group of scientists to study such a rich collection of stellar streams, measuring the speeds of stars using the Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT), a 4-meter optical telescope in Australia. Li and her team used the Doppler shift of light, used by the police radar guns to capture speeding drivers, to find out how fast individual stars are moving.

Unlike previous studies that have focused on one stream at a time, “S5 is dedicated to measuring as many streams as possible, which we can do very efficiently with the unique capabilities of the AAT,” comments co-author Professor Daniel Zucker of Macquarie University.

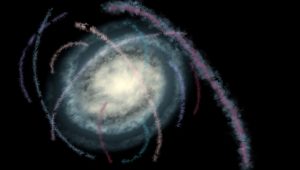

Artist’s impression of 12 stellar streams observed by S5, seen from the Galactic South Pole (Credit: Geraint F. Lewis, S5 Collaboration).

The properties of stellar streams reveal the presence of the invisible dark matter of the Milky Way. “Think of a Christmas tree”, says co-author Professor Geraint F. Lewis of the University of Sydney. “On a dark night, we see the Christmas lights, but not the tree they are wrapped around. But the shape of the lights reveals the shape of the tree,” he said. “It is the same with stellar streams – their orbits reveal the dark matter.”

A crucial ingredient for the success of S5 were observations from the European Gaia space mission. “Gaia provided us with exquisite measurements of positions and motions of stars, essential for identifying members of the stellar streams” says Dr. Sergey Koposov, reader in observational astronomy in the University of Edinburgh and a co-author of the study.

As well as measuring their speeds, the astronomers can use these observations to work out the chemical compositions of the stars, telling us where they were born. “Stellar streams can come either from disrupting galaxies or star clusters,” says Professor Alex Ji at the University of Chicago, a co-author on the study. “These two types of streams provide different insights into the nature of dark matter.”

According to Professor Li, these new observations are essential for determining how our Milky Way arose from the featureless universe after the Big Bang. “For me, this is one of the most intriguing questions, a question about our ultimate origins”, Li said. “It is the reason why we founded S5 and built an international collaboration to address this.”

Li and her team plan to produce more measurements on stellar streams in the Milky Way. In the meantime, she is pleased with these results as a starting point. “Over the next decade, there will be a lot of dedicated studies looking at stellar streams,” Li says.

“We are trail-blazers and pathfinders on this journey. It is going to be very exciting!”

__________________________________________________________________________________

The results of this work have been accepted for publication in the American Astronomical Society’s Astrophysical Journal. A preprint of the accepted version can be found here.

For comment on the paper, contact:

Professor Ting Li

Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of Toronto, Canada

ting.li@astro.utoronto.ca

For additional information, contact:

Meaghan MacSween

Communications Officer, Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics

University of Toronto

meaghan.macsween@utoronto.ca

Hi-resolution multimedia materials are available at:

https://s5collab.github.io/one_dozen_streams_press_release/

The Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Toronto is an endowed research institute with over 80 faculty, postdocs, students, and staff, dedicated to innovative technology, groundbreaking research, world-class training, and public engagement.

The research themes of its faculty and Dunlap Fellows span the Universe and include: optical, infrared and radio instrumentation, Dark Energy, large-scale structure, the Cosmic Microwave Background, the interstellar medium, galaxy evolution, cosmic magnetism and time-domain science.

The Dunlap Institute, the David A. Dunlap of Astronomy and Astrophysics, and other researchers across the University of Toronto’s three campuses together comprise the leading concentration of astronomers in Canada, at the leading research university in the country.

The Dunlap Institute is committed to making its science, training, and public outreach activities productive and enjoyable for everyone of all backgrounds and identities.